Great War Dundee

This is Dundee's story of those that served in the First World War, and of the people left at home

- At the Front

- Dundee’s Own

- Battle of Loos

- Ranks, roles and jobs

- Daily life at the front

- The War at Sea

- HMS Vulcan and the 7th Submarine Flotilla

- ‘Dundee Ladies Drowned.’ U-boats and Surface Raiders

- ‘Every shot was a hit!’ HMS Dundee and the North Sea Blockade

- ‘Engaged submarine with gunfire.’ HMS Perth and the Red Sea Patrol

- Sea Soldiers. HMS Unicorn and the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve

- North Sea Patrol. Royal Naval Air Station Dundee

- Commemoration. The Roll of Honour and Seamens’ Memorial

- Letters to and from home

- Dundee facts about WW1

- 5 myths of WW1

- Brave Animals

- Cemeteries and memorials worldwide

‘Dundee Ladies Drowned.’ U-boats and Surface Raiders

Among the first ships lost during World War One was the Ellerman cargo liner City of Winchester which, along with her cargo of jute for Dundee manufacturers Low and Bonar, was sunk by an enemy surface raider in the Indian Ocean two days after war broke out. The Dundee steamer Den of Crombie and the Dundee-built Californian, famous for her role in the 1912 Titanic disaster, were sunk off Crete in November 1915, the Oronsay was sunk near Malta on 28 December 1916 and 49 died when the Clan Farquhar was torpedoed off Tunisia while on passage from Calcutta to Dundee in January 1917. Brocklebank’s Malakand was torpedoed as she approached the English Channel in April 1917 and the Clan Cameron was sunk south of Portland Bill on 22 December 1917.

Passenger ships were initially protected from surprise attack by the ‘Cruiser Rules’, protocols designed to protect civilian life at sea agreed by the major maritime powers, Germany included. But the rules quickly eroded under the stress of oceanic trade war, most notoriously with the torpedoing of the Cunard liner Lusitania in May 1915. The 1,198 Lusitania victims included Dundonians James Mitchell, Norah Clark, George Nicoll and Alexander Harkins.

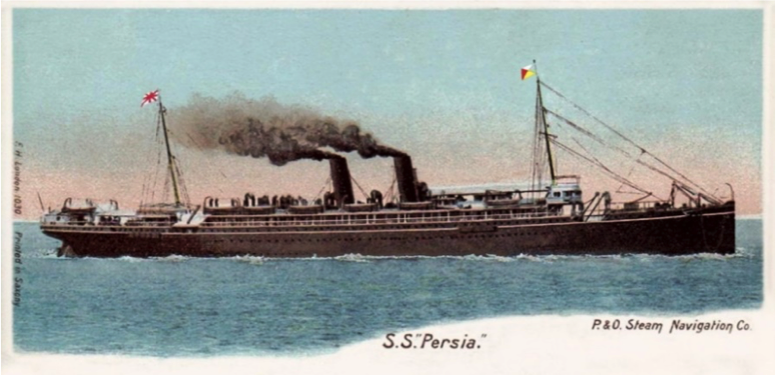

Among the 343 drowned when the P&O liner Persia was torpedoed south of Crete on 30 December 1915 were Dundonians Celia Ross, her two-month-old baby Elizabeth and jute mill manager Tom Burns and his wife Cecilia. Alexander Clark, Cecilia Burns’ brother-in-law, survived by clinging to an upturned lifeboat for thirty-two hours.

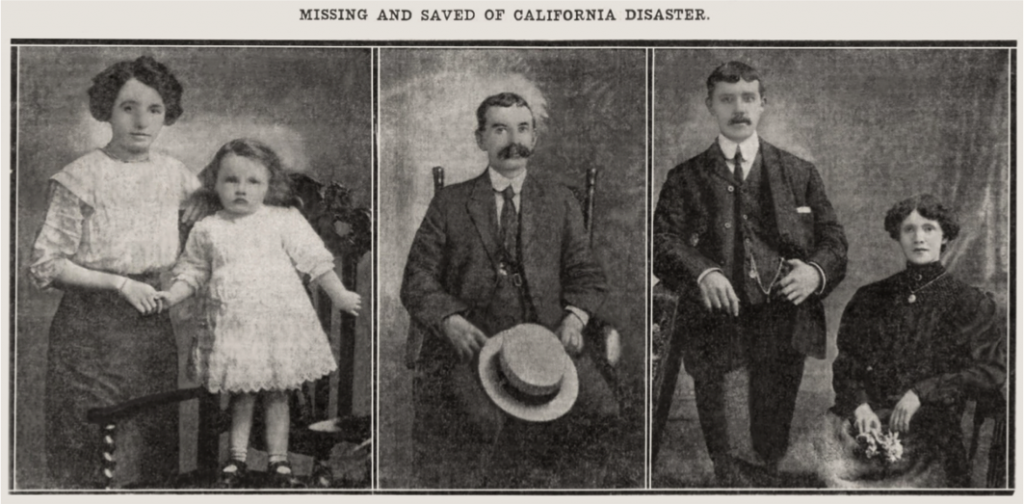

Worried about the reaction in Washington to the loss of neutral American lives, not least the 128 US citizens who went down with Lusitania, Germany withdrew its U-boats in September 1916. But it was becoming imperative that Britain be starved into submission before, as now seemed likely, America joined the war, so Germany restarted unrestricted submarine warfare in January 1917. The Glasgow-registered Anchor liner California, one of the first victims of renewed unrestricted submarine warfare, was torpedoed and sunk by U-85 south-west of Ireland on 7 February 1917. Among the 43 who drowned were Alice Smith, the daughter of Dundee coal merchant Robert Anderson, and her four-year-old daughter Edna. Alice had emigrated to Canada in 1911 with her husband Edward and Edna had been born in Calgary in 1913.

Other victims of the California sinking included Alice Smith’s friend Jane Kidd. Originally from Charles Street in Dundee, 26-year-old Jane had emigrated in 1909, married Dundee-born labourer Robert Kidd and settled in Calgary where Robert worked in the building trade. Jane’s body was recovered and buried at the Eastern Cemetery, Dundee. Her husband Robert, wounded while serving with the Canadian forces on the Western Front, was unable to attend. Thirty-year-old Marjory Robertson, a former jute worker from the Hilltown who had gone to Canada in 1915 and worked in a Toronto munitions factory, was also drowned. Her body was washed up on Inishbofin, a remote island off the coast of Galway three months after the sinking. She could only be identified by a locket and was buried on the island.

It seems likely that all three women and Edna were in one of the first lifeboats to be launched. California was still travelling forward and the lifeboat was dragged under the listing liner’s stern and swamped, pitching all on board into the sea. Survival time in the freezing North Atlantic in winter can be measured in, at best, minutes.

The sea war came closest to home when the jute liner Clan Shaw sank on 23 January 1917 after hitting a mine laid by a U-boat in the entrance to the Tay. Two of her crew, Sulaiman Sharaf Ali and Maula Bakhsh Sadruddin, died. Seven months later, on 21 August 1917, there were more large explosions in the entrance to the Tay as Royal Navy minesweepers depth-charged another minelaying U-boat at work off Tentsmuir. UC-41 was destroyed and Oberleutnant zur See Hans Förste and his 26 crew were killed. Eight men died the following day when the minesweeper HMS Sophron hit one of UC-41’s mines and sank.

Four ships were damaged when they struck the poorly marked Clan Shaw wreck and the Evening Telegraph commented that, ‘If the Clan Shaw is left a little longer, she will soon rival the record of a crack U-boat in damaging Britain’s merchant fleet.’ Dundee Harbour Trust faced damages claims amounting to well over £40 million in today’s terms and was in acute financial difficulty until the city’s MP, Winston Churchill, intervened to whittle the claims down to a manageable sum. The city promptly showed its gratitude by voting him out of office. Divers had meanwhile discovered, lying next to the sunken jute liner, the wreck of the naval drifter Leonard which had disappeared in bad weather early in January 1920. Leonard had clearly gone down after striking the Clan Shaw; no trace of her nine crew was ever found.

One of the last Dundee-bound ships to be sunk during the Great War was the elderly coaster Prunelle torpedoed in the North Sea. Twelve of her crew died, among them her Second Officer, 51-year old Alfred Cheetham from Hull. One of the most experienced polar sailors of his generation, ‘Alf’ Cheetham had sailed on the relief ship Morning during Scott’s Discovery expedition, on Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition and on Scott’s ill-fated Terra Nova expedition between 1910 and 1913. In 1914 he had joined Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition as Third Officer of the Endurance and played a key role in the survival epic that followed the crushing of the ship in the ice. Today, Alf Cheetham, one of the final victims of Dundee’s sea war, is remembered on a plaque in Paragon Station, Hull.